Dreams of Virtual Reality

Growing up as a child of the 80s, there was no day more sacred than Saturday. Mornings free from your parents; relaxing in your footie pajamas with your third bowl of cereal, only inches away from the flickering tube. For me, the day saved the best for last in the form of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

An avid sci-fi fan, my brother and I cut our teeth on campy Doctor Who villains, Max Headroom and all the troubles that come from the furry companionship of Tribbles. Unlike all the other shows to come before, Captain Picard and his crew of the USS Enterprise captured our imagination because the futuristic technology on the show seemed to be just over the horizon.

My favorite of these was the Holodeck, which transported you virtually to any time or place with the use of “hard holograms” projected in a tiny room on the ship. Not only was it a convenient plot devise, but its presentation of virtual reality (VR) seemed only a few steps away from the technology in my Nintendo Power Gloves. Star Trek was one of the first exhibitions of VR to the masses, but it actually started hundreds of years earlier thanks to architecture.

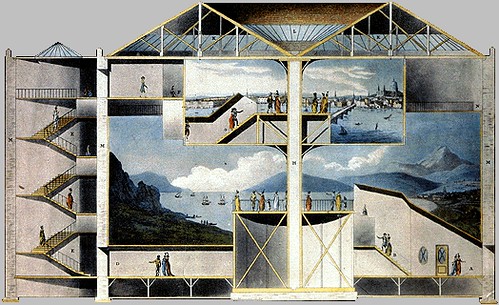

Beginning in the late 18th century, panorama paintings were made famous by the English painter Robert Barker. Following the success of such paintings as his Panorama of Edinburgh from Calton Hill, Baker commissioned architect Robert Mitchell to design the rotunda in Leicester Square for the purpose of displaying his life-sized paintings. There, Barker’s panoramas could be mounted to the interior wall of the rotunda giving the visitor a 360-degree-view of his paintings.

Stationed on a platform at the center of the rotunda, the panorama engulfed the visitors in military battles, urban vistas or beautiful gardens. Trump l’oeil and forced perspective were tricking the eyes of the public in both paintings and architecture dating back to the times of the Greeks and Romans.

Little changed in the techniques until 1838 with Charles Wheatstone’s research on stereoscopic vision. Wheatstone capitalized on his research with the invention of the stereoscope, which presented the left and right eyes with slightly different perspective images. These images are then combined in the brain to give it the illusion of three dimensions.

With the rise of personal computing in the 80s, VR technology took another large step toward the Holodeck of our dreams. Instead of 35mm film wheel, futurists and inventors imagined a 3D world within the computer where moving graphics would respond to the user’s movements.

Hollywood saw limited success in the 1992 dystopian sci-fi movie The Lawnmower Man, but much like VR of its time, it was disappointing in its depth. Suffering from slow graphic processing and a lack of resolution, VR was doomed before it found anything more than a cult following.

With the rise of the internet, the computer industry turned away from VR; however, Facebook’s acquisition of virtual reality company Oculus in 2014 for $2 billion sent shockwaves through Silicon Valley and signaled the return of the virtual world.

Now that small powerful processors and screen resolutions have become more finely detailed than the eye can perceive, all the major players in mobile technology are coming out with VR platforms this year. By 2020, VR is projected to pull in $150 billion in revenue.

Not All VR is the Same

Before shucking out thousands of dollars on a VR system, it’s best to understand the three distinct categories a system will fall under.

360 Degree Photos/Video

Much like the rotunda in Leicester Square, the viewer’s position is fixed within a stereoscopic 360 degree photo or video. Motion tracking of the viewer’s head allows them to look around and experience the world around them. The most popular of this platform is Google Cardboard. Working with any smartphone and a stereoscopic app, the user can insert their phone into the cardboard viewer similar to the old View-Master and suddenly be transported to a virtual world. Cheap and open-source, Google Cardboard viewers have flooded the market with options as affordable as $10 and enough apps to fill up your phone.

- Major platforms: Google Cardboard, Samsung Gear

- Do-it-yourself: www.google.com/get/cardboard/developers

- News: www.nytimes.com/newsgraphics/2015/nytvr/

- Entertainment: www.youtube.com/channel/UCzuqhhs6NWbgTzMuM09WKDQ

Augmented Reality

Testing the limits of current processing power, augmented reality uses stereoscopic cameras mounted in a headset to present VR elements within the physical real world. Tracking the user’s location and motion, the user is free to walk around in their environment as the virtual elements respond and adjust as to appear as real-life objects. This combined environment can then be manipulated using hand gestures and voice control.

- Major platform: Microsoft Hololens

- Do-it-yourself: www.microsoft.com/microsoft-hololens/en-us

- Apps: www.microsoft.com/microsoft-hololens/en-us/apps

Virtual Reality

Seen as the “true” virtual reality, the user looks through a stereoscopic headset into a 3D computer world. Motion tracking of the user’s head and body, provide a computer generated world where they can walk around, explore and interact with the use of a gamepad or special Oculus Touch controllers.

- Major platform: Oculus Rift

- Take a test drive: www.oculus.com/en-us

- Explore: www2.oculus.com/experiences/rift

The Future of VR and Architecture

No matter what platform rises to the top over the next few years, it’s interesting to see the implications on architecture. VR and 360 video have already made traction in the traditional 2D architectural rendering market. Rendering companies such as Seattle’s own Studio 216, have seen the opportunity and pivoted from standard 2D renderings to immersive 3D worlds.

Spurred by the hot technology market in Seattle, developers such as Skanska Commercial Development, are turning to 360 degree renderings and animations to set themselves apart and to speak directly to the tech workers. The future of augmented reality is following closely behind, and will soon allow designers the virtual space to create buildings in real time, explore building massing much like a sculpture and collaborate with global consultants around a virtual building.

Much like computer aided drafting (CAD) and building information modeling (BIM) rocked the foundation of architecture (pun intended), VR is set to be the next big change in how we design, document and sell our to work clients. As architects, we think visually and design in 3D, but are forced to flatten those creations into 2D.

This process of 2D translation is time consuming and results in a product that can only be fully appreciated by those trained in its vocabulary. Products like Hololens, provide us a world where the 2D translation is made obsolete. Consultants, clients and the general public will soon be able to immerse themselves in the design process and do it in a way that is as natural as a sculptor with their clay.

Just like I did as a 10-year-old, I imagine, one day in the future, walking into a room where the world bends to my will. Virtual elements appear and move into place with just the motion of my hands. Space is created and manipulated in real time all around me and where the only limit is my imagination. Thanks to the new crop of VR systems hitting the market this year, this tantalizing future is only years away, and I will finally get to realize my dream of boldly going where no architect has gone before.